Research uncovers new clues to reproductive cells’ quality assurance program

ANN ARBOR — Connectivity between reproductive cells — or germ cells — in males serves as a quality assurance mechanism by making clusters of cells more sensitive to damage, researchers at the University of Michigan Life Sciences Institute have found.

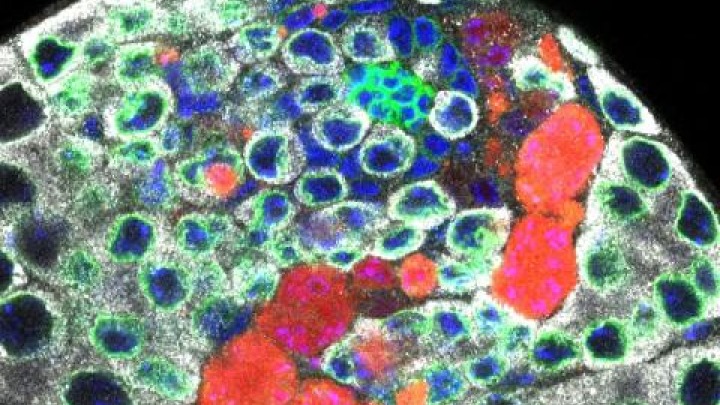

Scientists have long known that germ cells in the gonad form connected groups, called germ cell cysts, which allow the individual cells to communicate with each other. This feature is found in organisms ranging from fruit flies to humans.

“Several studies have looked into how they are connected, but nobody has been able to answer why they are connected,” says Yukiko Yamashita, Ph.D., a faculty member at the LSI, where her lab is located.

A new study conducted using fruit flies, published Aug. 15 in eLife, offers an explanation: quality assurance — a discovery made by Yamashita and graduate student Kevin Lu while working on a different project.

Germ cells in both ovaries and testes form cysts with a shared cytoplasm. A structure called the fusome acts as a cable within the cyst, connecting the cells and allowing them to communicate.

In ovaries, germ cells eventually differentiate into one oocyte, or egg, and several supporting nurse cells. This known differentiation explains why the germ cells need to be connected in female gonads — the nurse cells support the oocyte through their connected cytoplasm.

But in males, each germ cell develops into a sperm cell. All cells within the germ cell cyst are equivalent, so the reason why the cells needed to connect and communicate was unclear.

'And then we suddenly saw it'

Lu — a member of Yamashita’s lab and a student in the U-M Medical School’s Cellular and Molecular Biology Program — stumbled upon the explanation while irradiating cells for an unrelated project. He noticed that the connected cells were dying more frequently in response to DNA damage from radiation.

“And then we suddenly saw it,” says Yamashita, who is also an associate professor of developmental and cell biology at the U-M Medical School and a Howard Hughes Medical Institute investigator. “The connectivity was increasing their sensitivity to damage.”

The fusome within the germ cell cysts allows the cells to communicate about the total amount of damage across the cyst of cells, rather than the amount done to just a single cell. When the threshold for DNA damage has been met, all of the cells in the cyst die.

“Let’s say X amount of DNA damage in one cell will cause that cell to die. Once the cells are connected, now X amount of damage across the whole cyst will cause all the cells to die,” Yamashita explains. “The acceptable amount of damage per cell becomes much, much lower.”

The increased sensitivity means only the highest-quality cells survive. And this quality assurance is crucial, since germ cells are the only cells that get passed to the next generation.

“The communication through the fusome allows the body to be much more stringent in deciding which cells will make the cut to move to the next generation,” Yamashita says.

Yamashita holds up the finding as an example of why basic research is so important. While the significance of the finding in terms of therapeutic applications is not yet clear, it provides key information about how germ cells function and survive. And understanding germ cells may provide important information for understanding cancer.

Cancer cells often hijack germ cell mechanisms to achieve cell immortality. Thus, Yamashita emphasizes, “if we can really understand the germ cell, we are also going to learn a lot about cancer. And if we want to cure a disease, we first have to fully understand it.

Read the Article

Germ cell connectivity enhances cell death in response to DNA damage in Drosophila testis, eLife. DOI: 10.7554/eLife.27960