Cancer cells borrow healthy cells’ tools for moving around, but not in the way scientists expected

Cancer cells and healthy cells both employ the same set of molecular “scissors” to travel through tissues within the body — but they do so using very different processes, according to new findings from the University of Michigan published in Developmental Cell.

To invade neighboring tissues and branch out into blood vessels, cancer cells highjack processes that healthy cells also use to branch and migrate during normal development. Researchers in the lab of U-M Life Sciences Institute faculty member Stephen J. Weiss, M.D., investigate how these processes work in normal tissues to glean insights into how cancer manages to spread to distant sites in the body during metastasis.

For this study, postdoctoral fellow Tamar Feinberg, Ph.D., and her colleagues studied mouse mammary gland development as a model system to better understand how normal tissues develop the elaborate branching structures that cancer cells misuse to metastasize.

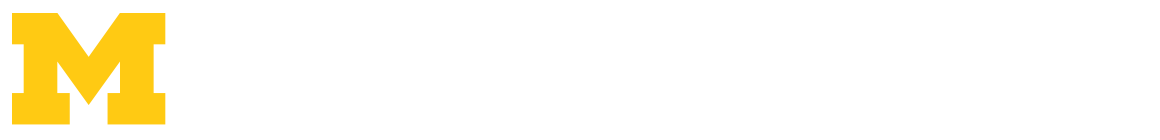

As breast tissue develops, cells within the mammary glands — called epithelial cells — have to branch out in order for the tissue to form the network of tubes that deliver milk to offspring. But before they can move, these cells have to cut through an intervening web of connective and structural tissues, termed the extracellular matrix, to clear the path to travel.

“They can’t just squeeze through the holes in this dense thicket,” says Feinberg, the lead author of the study. “You can think of the extracellular matrix as the dense material that makes up a kitchen sponge, but without any holes. To move through this tissue, a cell has to actually clip its way along to make enough space for it to navigate.”

Clearing the path

Weiss’ lab previously identified a single molecule called MT1-MMP (for membrane type-1 matrix metalloproteinase) that cells use as a sort of molecular scissors to cut through the extracellular matrix, but its role in development or cancer remained highly controversial.

To determine whether mammary glands use MT1-MMP during development, Feinberg and her colleagues decided to use genetic tools that enabled them remove the molecule from specific cell types, while leaving it functional in other cells.

Working with mouse mammary glands, the researchers first removed MT1-MMP from only the epithelial cells.

“Based on early experiments we performed with isolated tissues in culture, it’s been a common assumption in the field that epithelial cells might need MT1-MMP to move through the extracellular matrix in living animals,” explains Weiss, who is also the E Gifford and Love Barnett Upjohn Professor of Internal Medicine and Oncology at the U-M Medical School, and the study’s senior author. “They are the cells that are moving, so everyone — including us — thought that they must be the ones using the MT1-MMP to cut their way out. We wanted to test that.”

To their surprise, the researchers found that the glands lacking epithelial cell MT1-MMP were still able to branch.

In fact, the epithelial cells are not using the scissors at all. Rather, cells that reside in the connective tissue surrounding the moving epithelia, termed stromal cells, are doing the actual cutting, thereby clearing a path that allows the epithelial cells to move along. When the researchers deleted MT1-MMP from only the stromal cells, the branching came to a halt.

"It's sort of like a train moving through a tunnel. The train didn't clear the path; someone else dug the tunnel for it,” Feinberg says.

Disconnect between normal development and cancer

Even more surprisingly, the researchers found that the exact opposite was true for cancer cells. When MT1-MMP was deleted from the stromal cells surrounding the cancer cells, the researchers saw no effect on the cancer’s ability to invade local tissues or metastasize. But when the molecule was deleted from the cancer cells themselves, they could not spread into surrounding tissues or blood vessels.

Importantly, using human breast cancer biopsies, Feinberg and her colleagues provide further evidence that human cancer cells use MT1-MMP to spread through tissue.

“It’s really a difference between controlled invasion and uncontrolled invasion,” Feinberg says. “We found that the same molecular scissors are required for both processes, but they are being used in completely different ways.”

Feinberg emphasizes that the model can still provide useful information about what factors may be important in tissue — and cancer — development.

“I think it’s important to address the disconnect between development and cancer,” she adds. “There may be similar situations with other tumor models and normal developmental processes.”

Go to Article

Divergent matrix-remodeling strategies distinguish developmental from neoplastic mammary epithelial cell invasion programs, Developmental Cell. DOI: 10.1016/j.devcel.2018.08.025