New understanding of immune cells’ role in driving liver disease points to a potential therapeutic target for NASH

Researchers at the University of Michigan have discovered how one type of immune cell may be driving, rather than combatting, liver disease in mice. Their findings, published March 13 in Science Translational Medicine, identify a possible target for preventing or reversing the progression from steatotic liver disease to the more deadly non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH)

Steatotic liver disease — the accumulation of extra fat in liver cells — is a relatively benign condition estimated to affect 25% to 30% of the adult population in the United States. Up to one-third of those cases will develop into NASH (also referred to as MASH, for metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis), which results in liver damage and can lead to cirrhosis and cancer.

“There are no FDA-approved drugs to treat or prevent NASH,” says Jiandie Lin, Ph.D., a professor at the U-M Life Sciences Institute who led the new research. “So there is a great medical need to determine what exactly is happening to drive NASH and whether there are potential targets where we could intervene therapeutically.”

Lin’s team has now uncovered how the damaged liver cells themselves set off a chain reaction that results in further inflammation and further tissue damage —ultimately snowballing into NASH — by recruiting immune cells best known for fighting infections and repairing injured tissues.

“We’ve uncovered a pathway that appears to operate in macrophages to worsen the demise of liver cells ... By specifically targeting MS4A7, we may be able to unlock a new therapeutic avenue to alleviate NASH.”

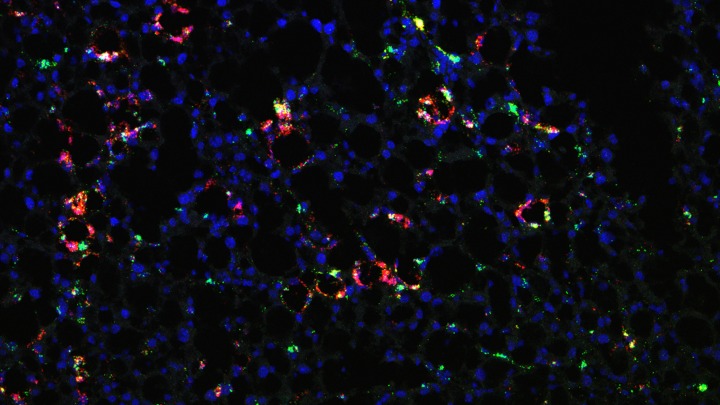

The team previously discovered that, compared with healthy mouse livers, livers from mice with diet-induced NASH contained substantially higher proportions of immune cells called TREM2+ macrophages, a type of white blood cell marked by production of TREM2 (“triggering receptors expressed on myeloid cells 2”) protein.

“TREM2+ macrophages are found in many human disease conditions, including cancers and neurodegenerative diseases, and are commonly linked to chronic tissue injury,” explains Lin, who is also a professor of cellular and developmental biology at the U-M Medical School. “But what prompts these macrophages to appear? During NASH, is this adaptive response where they arrive to help with healing? Or are they potentially facilitating the progression of the disease? These are the types of questions we are trying to answer.”

A hallmark of steatotic liver disease is the accumulation of fat inside liver cells, in the form of lipid droplets. As the condition worsens, and liver cells become injured or die, and the lipid droplets leak out.

Lin and his team hypothesized that those loose lipid droplets could serve as an alarm signal that leads to the recruitment of immune cells — particularly macrophages, whose job is to find and digest foreign entities in the body — and initiation of inflammatory response at the site of injury.

To test their theory, they introduced isolated lipid droplets into the mice and found that the droplets immediately triggered macrophage infiltration into the liver and subsequent maturation into TREM2+ macrophages. In mice with pre-existing NASH, lipid droplet exposure exacerbated the severity of the disease.

How TREM2+ macrophages contribute to NASH progression remains elusive. To shed light on this important question, the researchers performed single-cell gene expression analysis to identify other signature proteins within this macrophage population.

They observed that, in both mice and humans with NASH, a protein called MS4A7 is highly expressed by TREM2+ macrophages in the diseased liver. When the team deleted the MS4A7 gene from macrophages in mice, animals fed a NASH diet were more protected from liver injury and disease progression.

Through a series of experiments, they determined that MS4A7 over-activates the inflammatory responses that are normally used to kill bacteria or viruses, and turns them against the body’s cells — in this case, liver cells.

“We’ve uncovered a pathway that appears to operate in macrophages to worsen the demise of liver cells,” Lin says. “This population of macrophages seems to play multiple roles in the setting of NASH. By specifically targeting MS4A7, we may be able to unlock a new therapeutic avenue to alleviate NASH.”

Top image: Macrophages in fatty liver (red and green); blue marks the nuclei. Image credit: Linkang Zhou and Jiandie Lin, U-M Life Sciences Institute.

“Hepatic danger signaling triggers TREM2+ macrophage induction and drives steatohepatitis via MS4A7-dependent inflammasome activation,” Science Translational Medicine. DOI: 10.1126/scitranslmed.adk1866